A good system of grazing is one that uses livestock behavior to sustain forage and animal production at a low cost. No single grazing system will be suitable for all locations or meet the needs of all producers. Certain tracts of land lend themselves to one type of grazing system better than others. Different philosophies or experience levels of grazing managers will also influence how livestock are manipulated. Grazing management involves controlling where, when, and how much livestock graze. Grazing systems give you a structure for doing just that. Choosing the right grazing system for your land and livestock is one part of being a good grazing manager.

Grazing Systems

Grazing systems are generally designed to improve animal production by improving the health and production of forage. Using the right grazing system for your forage lowers grazing pressure and creates opportunities for desirable species to grow. Other common grazing system goals are to meet nutritional needs of animals, lower stress on livestock, and minimize supplemental feeding while protecting habitat for wildlife and keeping labor costs down. If this sounds like a lot to balance, that’s because it is! But finding a grazing system that meets your goals will improve the resilience of your livestock operation and reduce costs down the road.

Continuous Grazing

The most common grazing systems used today are continuous grazing and rotational grazing. Continuous grazing involves letting cattle graze a pasture long term, at a low intensity, with little to no rest for the plants. This provides a slightly better average daily gain per head but does not improve gain per acre. Continuous grazing is low-maintenance and requires less infrastructure (fences, watering troughs, etc.), making it a good choice in areas with forage types that can handle inconsistent grazing pressure and for producers who do not currently have the resources to invest in infrastructure. The disadvantage is that plants become more vulnerable to overgrazing and drought. To avoid overgrazing, the number of animals on the pasture needs to be adjusted (sometimes reduced) as conditions change year to year.

Rotational grazing

Rotational grazing involves periodically moving livestock between pastures or paddocks as they graze the available forage. This method increases gain per acre and overall forage yield by enabling repeated plant regrowth after grazing. Rotational grazing also helps distribute nutrient-rich manure and lowers the need for supplemental feed. Another advantage is that you have more control over the grazing intensity and rest periods for forage. This allows you to manipulate the herd movement to meet conditions rather than just the herd numbers. The catch is that it requires more infrastructure and time to direct movement between paddocks. The movement frequency and number of paddocks in a rotational system should be adapted to individual goals and management criteria. This may involve some trial and error. Systems can use anywhere between 2 to 16 or more paddocks depending on the needs and abilities of the producer and land. This system can have “add-ons” as resources become available – you can start by dividing a pasture into 2 paddocks and subdivide more pastures as resources become available. You might even use temporary fencing or troughs to try out new paddocks and rotations. This allows flexibility and experimentation to find the right fit.

Stocking Rates

According to Dr. Vanessa Corriher-Olson, of Texas A&M AgriLife at Overton, an important point to remember is that in both systems your most critical grazing management decision is still the stocking rate. There has not been a grazing system devised that will lessen the negative impacts of an overstocked pasture. While rotational grazing systems can handle higher stocking rates than continuous systems, they are both vulnerable when overstocked. Symptoms of overstocking include lower amounts of desirable forage, bare patches of dirt, and ant mounds or manure piles that are visible from a distance. Having too many animals on the land also reduces animal performance, encourages weed infestation, and results in more off-farm purchases such as herbicide and supplemental feed – starting a cycle of increasing inputs for decreasing gains. If your land also has a history of overgrazing, it may need even lower stocking rates than normal to allow time for desirable forage to recover. This is why knowing and applying the right stocking rate is important for operational sustainability and good grazing management.

Find Help

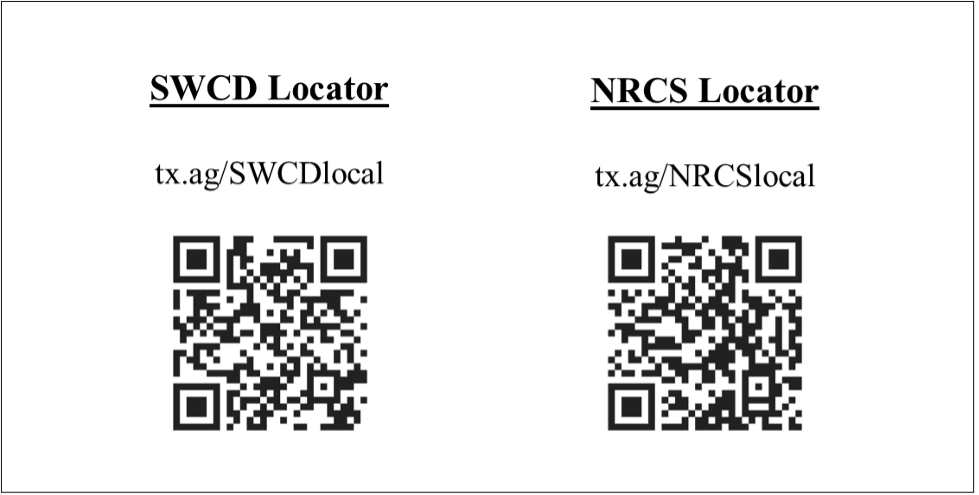

Grazing systems have become a hot topic of debate in grazing management. But don’t get caught up in the “analysis paralysis” of choosing the exact right one. Local conservation professionals can help you find the right stocking rate and develop a grazing plan that matches your situation and goals. Contact the SWCD or NRCS office in your county to make a free conservation plan that benefits your livestock operation. Your local county extension agent can be an excellent resource as well. Find your County Extension Agent. You can find your local NRCS or SWCD office by visiting the website links or scanning the QR codes below:

Vanessa Corriher-Olson, Ph.D.

Professor, Forage Extension Specialist

Texas A&M AgriLife Extension

Soil & Crop Sciences

Overton, TX